Portfolio Concentration: Separating Myth from Reality

An argument for more diversification and thoughts on portfolio construction

“Don’t screw up a perfectly good stock-market strategy by diversifying your way into mediocre returns.” — Joel Greenblatt

“Diversification may preserve wealth, but concentration builds wealth” — Warren Buffett

“If you can identify six wonderful businesses, that is all the diversification you need. And you will make a lot of money. And I can guarantee that going into a seventh one instead of putting more money into your first one is going to be terrible mistake. Very few people have gotten rich on their seventh best idea.” — Warren Buffett

You have probably heard these quotes before, and if you stopped your portfolio-construction research there you may put your money into 6 stocks and call it a day, after all, that is what some of the best investors recommend.

The common belief is that an intelligent investor should concentrate their money into a few of their best ideas. When diversification is brought up proponents will cite the quotes above and argue:

“Why put money into your 7th best idea”

“Diversification will water down your returns”

“No one can follow 30 companies closely enough to know them inside and out”

“You will only find 1 or 2 good opportunities each year”

In what follows, I will take one out of Rob Vinall’s playbook and challenge the widely held belief, a tenet of value investing, that a concentrated portfolio is superior to a more diversified portfolio.

For the purposes of this post I will define a ‘concentrated’ portfolio as one with less than 10 stocks and greater than 70% in the top 5 holdings. A more ‘diversified’ portfolio is one with between 10 to 30 stocks and less than 75% in the top 10.

Personally, I haven’t put more than 10% (by cost) into any one position, although I will allow them to grow past that.

For the record, I believe you can achieve exceptional returns with a concentrated portfolio OR a more diversified portfolio. Many strategies can work in investing and you’ll want to choose a strategy that aligns with your personality and temperament.

Arguments for Diversification

I have attempted to rank order these from most beneficial to least:

Optionality to buy companies with perceived risks;

Increase your odds of holding right-tail outcomes;

Timing problem;

Optionality to reweight between undervalued and overvalued holdings; and,

Risk (probability of loss) mitigation

Benefit #1 — Optionality to buy companies with perceived risks

If you only have 6 companies in your portfolio you really need to focus on the downside with every investment. Unfortunately, some of the biggest winners will have hair on them when you first find them.

Payfare, Zedcor, and TSSI are all companies I’ve bought that had/have significant customer concentration risk. Payfare lost their biggest customer this year and the stock fell 75%. On the other hand, TSSI and Zedcor gained enough in the year (each on their own) to offset all of my losses combined, including Payfare.

Consider $HIMS and $LMND → yes there is a chance Amazon wins telehealth e-commerce or that Lemonade incurs catastrophic insured losses but the upside in the most right-tail outcome is >100x and thus I think both opportunities present favourable Expected Values (asymmetry).

I would not have been able to hold any of these stocks in a concentrated 6-company portfolio (although some investors may).

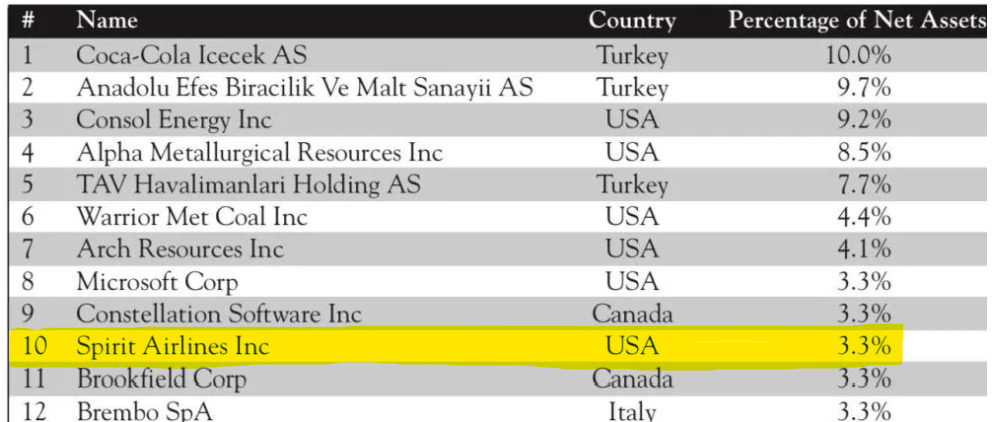

One final example from popular portfolio manager Mohnish Pabrai: Due to its structure, his new mutual fund holds more positions than his partnership and as a result he can hold investments with perceived risk. One investment he made was the arbitrage play on Spirit Airlines (which didn’t work out). He could not invest in this arbitrage as part of his partnership because the portfolio’s concentration necessitates higher holding percentages.

Source: Pabrai Wagon’s Fund Semi-Annual Report (as of June 30, 2024)

No one should fill a portfolio with these types of investments, but having a diversified portfolio allows you to include the best ones when you might otherwise have to forgo them.

Benefit #2 — Increase your odds of holding right tail outcomes

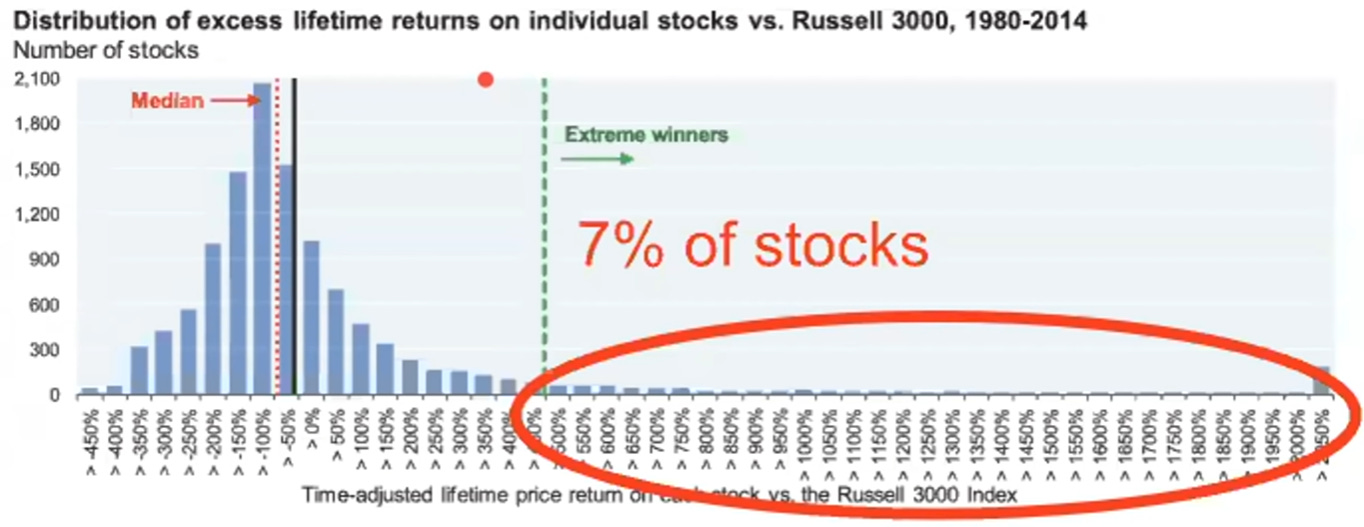

What does right tail mean? In investing the right tail represents the most extreme positive outcomes and highest returns, referring to the far right of a distribution.

Per the study below, few companies (~7%) drive positive stock market returns. The right tail is the companies circled on the right side of the chart.

Credit: JP Morgan and Brian Feroldi (who I first saw present it)

Having more companies in your portfolio increases the chance of finding and holding one of these outliers → 4 times more likely with a 20-company portfolio vs a 5-company portfolio.

You don’t have to be right on every pick, what matters is how much you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong.

Benefit #3 — Timing problem

If you aren’t an investor with a large following or avenues for promotion it can take longer for your companies to be discovered. Think about what happens when Warren Buffet buys a company: (1) he buys a new “cheap” company; (2) his 13F comes out after quarter-end; (3) the market researches the company; and (4) it will be discovered. You don’t even need a following as big as Buffett’s to have the same effect, especially in smaller market caps.

If you’re like me and don’t have a large following, you can invest in a company, write a post about it, but who knows when the general market will notice.

I hold about 25 companies that I think are undervalued, but I have no confidence in timing/guessing when the market will agree with me. So instead I hold them all and have the option to reallocate from names that are quickly discovered to ones yet to be discovered.

Benefit #4 — Optionality to reweight between undervalued and overvalued holdings

In general, I try to weight my companies by my conviction in each name. When a holding like Zedcor or TSSI double → triple → quadruple in a short period, and I think the company fundamentals could take time to catch up to the valuation, I have the option to reallocate funds to other companies. When you hold 25 companies and follow them closely, you will inevitably have some companies that look especially undervalued.

Having more options to put your cash to work also helps when making deposits to your portfolio.

A watchlist can be used similarly, but most don’t follow their watchlist as closely as the companies in their portfolio.

If you’re looking for extra reading on this topic, here is a great article by Turtle Creek who employ a similar approach of reweighting current holdings and have achieved >20% returns for over 20 years:

https://www.turtlecreek.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/TCAM-Thought-Piece-Edge-3-Portfolio-Construction-Apr-2013.pdf

Benefit #5 — Risk (probability of loss) mitigation

This is the first benefit people think of when you mention diversification, but I included this one last because (1) the additional risk mitigation you get going from 10 uncorrelated ideas to 30 isn’t huge; and (2) I do believe you can adequately manage risk with less than 10 companies so long as you focus on the downside of each investment.

Having more companies at lower weightings can mitigate the impact of losses from any one holding. For example, in 2024 one of my holdings Payfare dropped sharply after a negative press release, but since it was only a 7% position it didn’t really affect my annual results. Even if it went to $0 it would have only affected my portfolio a little over 7%.

This can be especially valuable for a new investor buying companies for the long-term because it takes time to build comfort that you know what you’re doing.

Arguments Against Diversification

Drawback #1 — “Why put money into your 7th best idea”

Because I don’t know which my top 6 ideas are and I especially don’t know the timing of when or if they’ll appreciate. Companies and their management are too complex and markets are too nuanced to precisely rank ideas.

Some of my biggest winners started in the bottom half of my portfolio.

Drawback #2 —“Diversification will water down your returns”

The more companies you hold the less impact each will have on your portfolio, so at some point you are diluting the quality of your ideas. I actually agree with this one to a point.

While it is difficult to pick an exact number for “how many companies is too many,” I think a good rule is that if you hold more than 30 companies you should be weighting new additions towards the long-term compounder category — the 7% right-tail type of companies where a small position can turn into a much larger one. To identify companies like these, I like to think to myself “is it plausible this company could 10x in the next 10 years?”

If you’re holding a portfolio of 100 “cheap” companies where the best outcome is a double, I think you will end up disappointed with your results.

Also, the more companies you hold the more important it is to focus on watering the flowers and trimming the weeds i.e. don’t average down as much as you average up.

Some examples of successful investors that hold a lot of companies are Peter Lynch (often mentioned when the topic of diversification is brought up), he is an extreme example and held hundreds of stocks with an annualized return of 29.2%. Francois Rochon, Brian Feroldi, and David Gardner are others.

Anecdotally, holding 25 companies hasn’t watered down my returns (yet): 2024 Results

Drawback #3 — “No one can follow 30 companies closely enough to know them inside and out”

You don’t need to follow them all as closely because the downside risk in any one name won’t ruin you. Do you really need to be the most knowledgeable person in the world on a 1% holding?

On the other hand, if you hold 6 companies you really need to hold them tight and maybe you should be talking to management for every holding.

One tip to optimize your time spent on research and analysis is ‘cloning.’ See the relevant excerpt below from a previous post of mine:

Explicit analysis = Fundamental/financial analysis and looking for red flags (table stakes, every investor must do this well to succeed)

Implicit analysis = Analysis of business quality, management, and industry/market (harder to teach and convey, I think this is where good investors can develop a sustainable edge)

In investment terms, "cloning" refers to the strategy of reviewing portfolios of successful investors or investment managers for ideas. Cloning is helpful because you can find managers whom (1) you trust are good analysts and (2) have some confidence that they put investments rigorously through their explicit filter.

Through cloning good investors we know that it is likely an investment will pass through our own explicit filter so we can focus more time on implicit analysis (intuition of quality).

Since explicit filtering takes longer than implicit, cloning is especially advantageous for a part-time investor because it saves time. However, even for a full-time investor the time savings increases the number of investable opportunities you are looking at and, since investing is really a game of opportunity cost, the more viable opportunities to compare against the better.

It is important to note that before making any investment it is still required to do a fulsome fundamental analysis yourself, cloning just lets you know which companies are likely to pass.

Drawback #4 — “You will only find 1 or 2 good opportunities each year”

Maybe this is true if you are limiting your search to large caps in the S&P 500/Nasdaq, but I disagree when we include all public companies. I see enough potential opportunities in micro and small-caps that I find ranking opportunities to the top ~25 has been a bigger problem than finding new ones (so far).

Conclusion

You don’t have to be right on every pick, what matters is (1) how much you make when you’re right and (2) how much you lose when you’re wrong. I believe a diversified portfolio helps in both of these respects.

I believe it also depends on where you are in your investment journey. As you grow more confident in your top six choices, it becomes easier to focus your funds in those areas. The earlier stages, in my opinion, are more about exploration and discovery.